Exodus 19-20

Introduction

This lesson covers from when Israel camps in the Sinai wilderness, to the Ten Commandments. Again, please refer to these resources as well: this commentary, the NETS Bible, and this LXX Interlinear.

This lesson covers from when Israel camps in the Sinai wilderness, to the Ten Commandments. Again, please refer to these resources as well: this commentary, the NETS Bible, and this LXX Interlinear.

Exo. 19

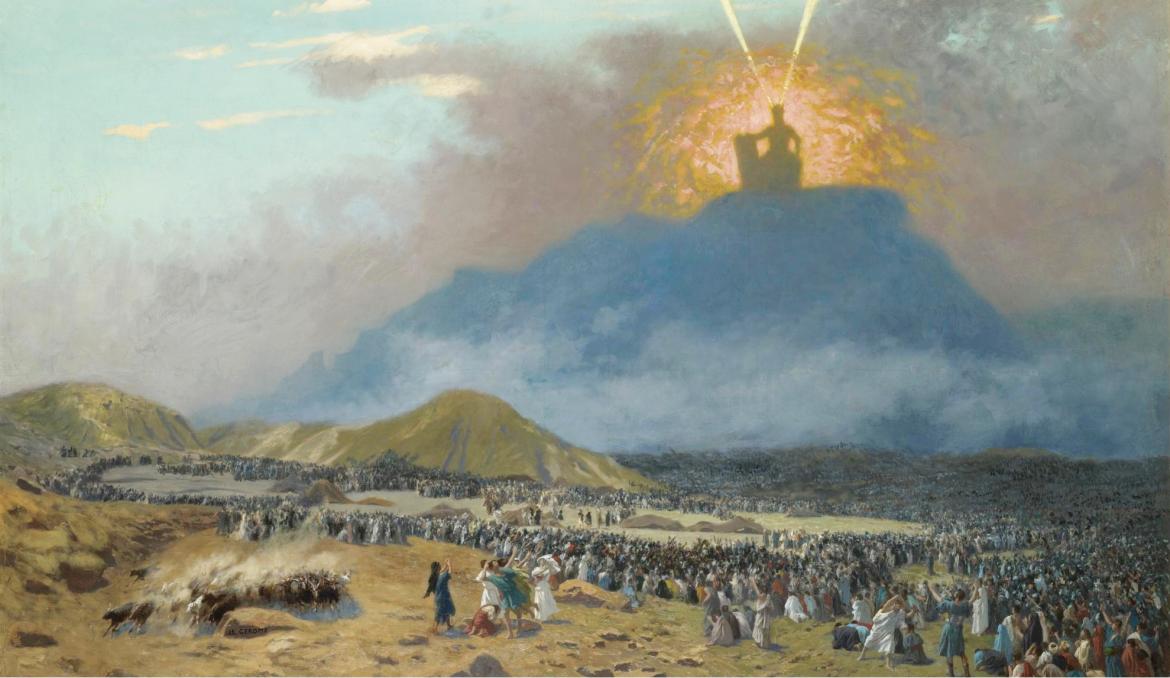

Three months after leaving Egypt, Israel reaches the wilderness of Sinai and camps at the foot of Mt. Horeb (aka Mt. Sinai in scripture), the mountain where Moses was first called by God at the burning bush. They will stay for a total of eleven months, according to most commentators who piece together events through the book of Numbers. And according to research at this source, Israel only actually traveled for about two years, and camped for 38 at Kadesh. There are some good maps there as well, along with the statement that Kadesh was near Petra, which may be the place of safety for the Judeans to run to halfway through the Tribulation. Both are near the south end of the Dead Sea.

And this section is where we first see the phrase in the Greek, “royal priesthood and holy nation”. We know this phrase from 1 Peter 2:9, and we remember that the New Testament quotes the Greek rather than the Hebrew, which here in Exodus is translated “kingdom of priests and holy nation”. Take a moment to review the covenants chart to remember where we are at this point.

Now back to Exodus, and we see that this is a conditional promise of God to “the house of Jacob and the people of Israel”― conditional because of the “if” in verse five. Heb. 8:6-13 cites the Old Testament as saying that the new covenant would be “with the people of Israel and Judah”. The whole purpose of the Jerusalem Council of Acts 15 was to answer the question of whether all Christians had to also be Jews, and the answer was “no”. But whether the church is the ultimate “royal priesthood and holy nation” is examined in Constable’s notes on 1 Peter 2:9 (pp. 44-46).

In this context, long before the church, the nation and people of Israel are the original recipients of this conditional promise. And as would eventually be explained in Gal. 3:12-25, its function was temporary and instructional, and of works rather than faith— a contrast between the unconditional covenant of Abraham and the conditional one of Moses. The blessings can extend to the world, but the covenant is with this nation.

After the people verbally agree to this covenant, Moses goes up to take their answer to God, who then tells him to go back down to the people and tell them to prepare themselves for a solemn, legally-binding ceremony to enact the covenant in writing. They are to purify themselves and wash their clothes. They must also keep away from the mountain on pain of instant death, and only approach it after they hear a trumpet blast from God and the pillar of cloud leaves.

They have 2 days to prepare, which Moses adds must include couples abstaining from intimacy. Most commentators take this as a matter of subduing the body’s cravings, and in the later laws we’ll see that most uncleanness has to do with body secretions of various kinds. What we can not conclude, as so many have done over the centuries, is that this command is saying women are inherently unclean and unworthy to be in God’s presence.

When the time comes for this to take place, the people are terrified by a loud trumpet and other loud sounds, along with lightning and darkness. It could be taken as something like a volcanic eruption by the description in verse 18, but the cause is again the miraculous presence and power of God. This is the first instance where God’s loud voice is equated with a trumpet, and the last will be in Rev. 1:10. Neither of these trumpets are of mere angels or have to do with judgment, but with the presence of God.

There is a conversation at this time between God and Moses, and God tells Moses and Aaron to come up but have everyone else stay at the bottom. This includes priests as well, though no priesthood has as yet been established. Ancient near east practice was that heads of families were de facto priests, and we’ve already met Melchizedek and Jethro as some examples. So the likely reason priests are singled out is because they may have thought themselves exempt from the command to keep their distance from the holy mountain.

Now we’re about to read the details of the covenant law, but before we do we should understand some points as brought out in Constable’s notes. There were two common types of covenants: parity (between equals) and suzerainty (between a sovereign and his subjects). Both took the form of a preamble, history, statement of principles, and consequences of obedience and disobedience. This covenant is of course the suzerainty type, and it contained three basic categories:

- Moral life

- Religious life

- Civil life

This hardly means that Christians can pick and choose to follow one category or another, or even dissect the Ten Commandments and discard the one that isn’t in any way repeated in the New Testament, so they can say they keep the law. Rather, it simply classifies the applications of the laws, but all were binding on Israel.

Exo. 20

Verses 1-2 comprise the preamble, identifying the “sovereign” and his proven power, and how the “subjects” owe him their allegiance. The first four commmandments will deal with how the people must relate to God, and the last six with how the people must relate to each other. Though various groups through history have divided the Ten Commandments differently, the numbering used unanimously by the early church was that with which most are familiar: that the first is “no other gods”, the second is “no idols”, and the commandment about coveting is one commandment rather than two.

Verses 3-6 are the first two commandments; the first means not that God is to be the chief one among many, but the only one. The second refers to no idols or likenesses of physical or angelic beings of any kind, for the purpose of being venerated as having divine power or ability. We see here that God says he is “a jealous God”, so we need to know the difference between jealousy and envy. Jealousy is protecting what is rightfully ours, but envy is desiring what is not rightfully ours. So God being jealous is not a bad or immoral quality at all.

Yet what about verse five, which speaks of God avenging sins for up to four generations of those who hate him, and mercy to thousands of generations of those who love him and keep his ordinances? And how would we reconcile this with Ezekiel 18, where especially verses 4 and 20 say that the one who sins is the only one who will die? Remember that God says this as part of the formal drawing up of the covenant, not mere poetry or hyperbole.

The answer is the difference between guilt and consequences. Here, God is referring to how those who hate God will invite very long-lasting consequences on their descendants, whereas in Ezekiel the topic is on being held guilty for what someone else has done. We all can relate to how one simple mistake or sin can affect us and our family and friends, and we have seen this for the whole nation of Israel, which of course will reach its extremes when they’re exiled as a nation in the future.

The third commandment (not taking the Lord’s name in vain) means to not use it as a casual or vulgar expression. The added warning seems to make this an unforgiveable sin, at least under the law, likely because it meant a person is treating God as worthless or shameful.

The fourth commandment is about keeping the Sabbath, which was the seventh day of the week from one sundown to the next. The reason in the immediate context is to remind them of creation week, which makes no sense if creation took many eons, and nothing in either the Greek or Hebrew indicates any such thing as “a day per an epoch”. And this rest meant that no one― slave or free, male or female, foreigners, or even animals― was to do any labor. The Bible also speaks of a future spiritual rest in both Testaments, in Psalm 95 and Heb. 3 and 4, and we’ve already seen God allude to this when he made the rule about not collecting manna on the seventh day. It’s interesting also that the Greek text says “remember the day of sabbaths” (plural). The context makes it clear that there is only one sabbath per week, so the meaning of the plural here is simply that this is a repeating cycle.

The fifth commandment is about children respecting their parents, because just as the whole nation owed its life to God, so also children owe their lives to their parents— both of them. As the New Testament points out in Eph. 6:2, this is the first commandment with a promise. This is not to say that parents are always sinless or perfect, but that children under their care should show them more honor than other adults, and especially more than themselves or their siblings. It is unwise to disrespect anyone we’re dependent on.

The sixth and seventh commandments really stem from the same principle: don’t take what doesn’t belong to you. The main distinction between adultery and fornication is that in the latter there is no one from whom the other person is being taken, except perhaps in a society where the daughter is considered the property of the father.

One point to make about stealing is that it requires such a thing as private property. The society God is structuring here is not a commune but an association of families owning their own properties, livestock, crops, equipment, and employees. Land ownership within tribes was especially important to God regarding the nation of Israel.

We could actually add the eighth commandment in the same category, since murder is the taking of a life that doesn’t belong to you. Critics like to point at this one and say that God violates it since he takes life, but life is his to give or take. Would the critics put themselves under the same rules as they put their own children? Rather, this commandment is to keep people from treating life as cheap or theirs to take without divine permission. Such permission was granted to society when Noah got off the Ark, but only if a person took another person’s life; it was never granted as a matter of personal vengeance or a way to solve differences.

Some even try to make the killing of animals murder, but the context here and throughout the scriptures never supports such a thing. Neither does it grant us the right to maim or torture people or animals, unless a person has maimed another person, and even then there is no permission to make the “eye for an eye” torturous. God has already delegated the authority to wage battle, but again, it is delegated, not to be taken upon ourselves.

The question often arises as well about suicide. But if we belong to God, then not even we can take our lives because they don’t belong to us. However, we also must show compassion since many suicides are the result of immaturity, severe suffering, or mental illness. Let God be the judge, but at the same time, let us be more intent upon showing concern such that others won’t even consider it. Prevention is far better than grief.

Now to the ninth commandment, bearing false witness. This is specifically about false accusations, not all statements of untruth. After all, God himself used cover stories in various times in Israel’s history, and he will send a “strong delusion” during the future Tribulation. But this is hardly a blanket endorsement of lying. Politeness and diplomacy are often borderline or outright lies, but they can prevent hostility or needless tension. Intent is everything; are we trying to harm or help? Slander is always harmful of course; its purpose is to ruin someone’s life or reputation for something they never did. Simply being offended or not liking a person is hardly justification for this.

The tenth and final commandment is against envy: not simply wanting something but having the desire to take it though the owner is not offering it for sale. In fact, all the commandments prohibit taking what is rightfully another’s, whether the other is people or God, objects or honor.

After all this, the terrified Israelites ask Moses to speak to God for them in the future, but Moses explains that this fear of God is part of the instruction. They have thus asked for intermediaries between themselves and God. Critics take this as an indictment against God, who in their judgment is immoral for wanting to be feared. But again we appeal to them as parents; do they not expect their children to fear punishment should they defy them? Parents give rules to protect and guide (ideally at least), so defiance can be dangerous or deadly. And if the children don’t learn by words, then they will have to learn by actions. When done with compassion and love, children raised in this way rarely fault their parents but respect them instead. And this is what God has repeatedly demonstrated, being reluctant to punish, but always having reconciliation and maturity as the goal.

Then in verse 24 God instructs them to make altars out of dirt or uncut stones, because the tools would defile them. They are also not to build the altars so high that anyone could look up the robes of the priests and shame them. These requirements were likely in response to the worship practices of other religions.