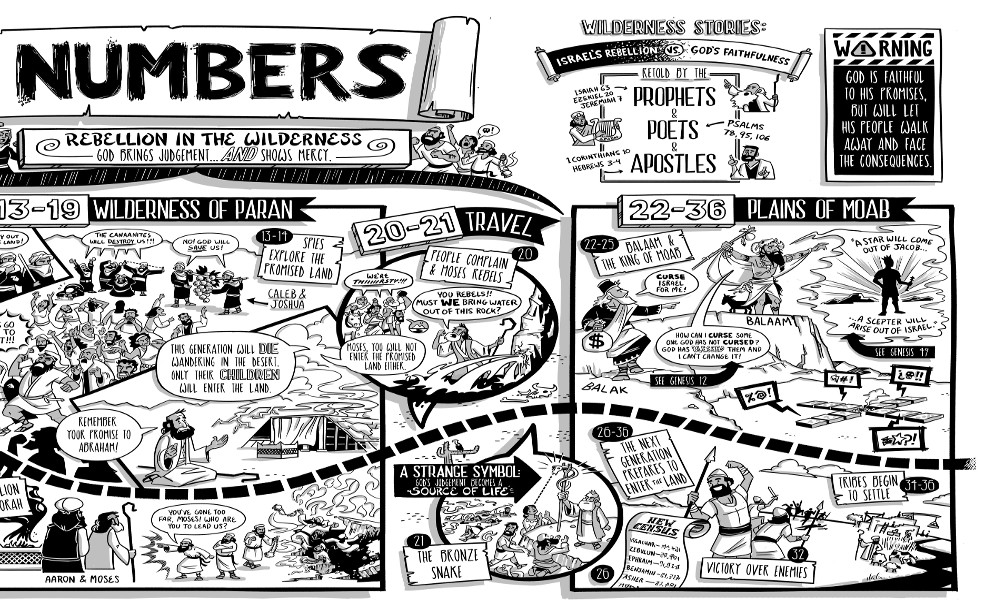

Numbers Highlights

Introduction

This lesson concludes our study of the book of Numbers. It covers from the plague of serpents to the end of the book, featuring the death of Aaron, the account of Balaam, and the sin with Moab. Please refer to these resources as well: this commentary, the NETS Bible, and this LXX Interlinear.

This lesson concludes our study of the book of Numbers. It covers from the plague of serpents to the end of the book, featuring the death of Aaron, the account of Balaam, and the sin with Moab. Please refer to these resources as well: this commentary, the NETS Bible, and this LXX Interlinear.

The death of Aaron

As Israel travels, Moses sends messengers ahead to the king of Edom to request passage through his land, but he refuses to allow it. While nothing more is said about it here, later on this refusal will be a factor in God’s judgments against Israel’s enemies. After going around them God tells Moses that Aaron is about to die, so he needs to pass on his priestly office to his son. He does so up on a nearby mountain for everyone to see, and immediately Aaron dies and is buried there.

The bronze serpent

After a victory over the Canaanite city of Hormah, Israel gets impatient having to go around Edom. So they decide this is a good time to whine about free food from heaven, because it’s boring. So God wastes no time in punishing them, in this case with poisonous serpents that kill many of them. The solution after they repent is for Moses to make a bronze likeness of one of the snakes and put it up on a pole, such that whoever looked in faith to it would be healed if they were bitten.

This is precisely what Jesus referred to in John 3:14. He too would be “lifted up”, and whoever looks to him in faith is saved. As always, God has reasons for what he does and commands, and he’s not obligated to explain every one of them to us as we often demand. Are any of us really better than Israel, when we keep forgetting what God has done for us, and how many times he’s forgiven us?

King Og

Israel keeps going after this, and you can see in Constable’s notes a map of the various people groups in Canaan, with the strongest being the Amorites. Ch. 21 is where we meet Og, king of Bashan, and they defeat him after the Amorites. There will be more detail about Og in Deut. 3, who is described there as a Rephaite— a giant.

Balaam

Now in ch. 22 we come to the account of Balaam. As Constable notes, commentators are divided over whether or not Balaam was a prophet of God. There is a good case made for “not”, but Balaam still appeared to know about the God of Israel and had at least a respectful fear of him. He was at the very least an influential and sought-after soothsayer, and what he was about to experience would certainly have made him reconsider his views of the supernatural.

As you can read in the passage, at first Balaam simply accepts God’s command not to go with the officials from Moab and curse Israel. But king Balak sweetens the deal, so Balaam waits again for God’s answer— not as though he really considered God as his own God, but that this was the God who was communicating with him. This time God lets him go with the officials, but he still has to refrain from cursing Israel.

But then God is upset that he goes with them, apparently because God meant for him to choose wisely rather than actually carry it out. So this is where we see the well-known incident of the talking donkey. The donkey sees the Angel of the Lord blocking the path and holding a drawn sword, so it goes off to the side to go around. But Balaam sees nothing and beats the donkey for straying. Then it happens again, this time with the donkey going to the other side and pressing Balaam’s foot into a wall, so he beats the donkey again. It happens a third time, and since there’s no place left or right to go, the donkey crouches down and gets another beating.

Though it isn’t clear in translation, the donkey was not actually enabled to talk on its own, but instead was operated by God like a puppet. The likely reason Balaam carried on the conversation as if talking to a person is because of his deep familiarity with the supernatural. The conversation is actually kind of funny:

- ”Why are you beating me?”

- ”Because you’re making a fool out of me! I’d kill you if I had a sword!”

- ”Have I ever acted like this before?”

- ”Um, no.”

Then God lets him see the angel, who says something just as comical: “If the donkey hadn’t tried to avoid me, I’d have killed you but let the donkey go!” Balaam is terrified of course, but God just repeats the command to say what he is told to say.

So in ch. 23 he finally meets up with King Balak, but though they arrange for the curse to be pronounced, it comes out a blessing instead. The king is pretty exasperated, especially since he already paid him, but he decides that the gods just need a little more appeasement. So they try it again in a different place, though to no avail.

In vs. 19 we see a very key statement: that God is not a man, as if he could lie or change his mind. This is a good statement to remember when people claim God is just an exaulted man, or is like the pagan gods. But the second blessing infuriates Balak so they try a third time. And again, another key statement in vs. 9: blessings on those who bless Israel, and curses on those who curse Israel. Can today’s anti-Israel Christians take such a risk, if they are convinced modern Israel is not part of God’s plans? Can they guarantee that the nation is completely fake and fulfills no prophecy?

Though Balaam tried 4 times to curse Israel, he not only kept blessing them but also prophesied details about their conquests and their enemies’ defeat. God has shown in this incident that he will dispense true messages even through the ungodly, even an animal. God is all about the message, not the messenger. If he decides to use someone who doesn’t meet our approval, who are we to get in the way?

Moab

Ch. 25 highlights another lesson for us today: great achievements are often followed by great failures. After all that has happened, Israel’s close proximity to Moab leads the men to chase after the heathen women, who invited them to their sacrifices. The order of the text is not chronological, so we have to look ahead to ch. 31 to see that this came at the instigation of Balaam, who had given up directly cursing them and turned instead to enticing them to curse themselves.

God tells Moses to arrest every leader in Israel who sinned with the Moabites, and publicly execute them. But while he’s still speaking, one of them brazenly brings a Moabite woman to his tent. So one of the priests grabs a javelin, runs into the tent, and impales both of them at once. God had brought a terrible plague on Israel, but this stops it— after 24,000 had already died.

Land disputes

Ch. 26 begins the final phase of Israel’s wandering, with the second census of men of fighting age, to also calculate the amount of land for each tribe. But just when many readers are chalking up another male-centric win, ch. 27 tells of five women who realize that their clan is about to be robbed of land just because their father left no male heirs. God tells Moses that the claim is valid and the women must be granted land. To this we could add the fact that Job also granted inheritance to his daughters. God will only go so far in accomodating social norms.

Preparing for the death of Moses

The text turns to the impending death of Moses, and God has him go up on Mt. Nebo to see the Promised Land that he himself would not be allowed to enter. Moses takes the news well, but likely at least partly due to all the grief he had endured in his life, especially as the deliverer of ungrateful and fickle Israel. Joshua is chosen to succeed him, but at this point the text turns back to the requirements of the feasts.

Along with the feasts we see more about vows, and again we see the lesser social (not spiritual!) value of women. Even so, a woman not viewed as the possession or “honor” of a man was responsible for her own vows. Of course, I strongly dispute Constable’s quoted statement that Adam was held responsible for Eve’s actions because of his silence. We have already seen in our study of Genesis that no such responsibility or authority existed before they left Eden. It is especially inappropriate to compare a parent-child responsibility with husband-wife. Possession of some humans by others was never God’s natural order.

Ch. 31 tells us that Moses has one final task to perform: He must see to it that Israel wipes out Midian. Among the slain is Balaam, whose clever plan finally caught up with him. And though most people balk at the taking of women and children as plunder, it would be more humane than either killing them or leaving them to fend for themselves.

But there’s a further complication here: Moses is angry that they failed to kill all the women. He reminds them that these women were the ones who had enticed them to sin, and that the boys would grow up, undoubtedly to avenge their fathers. So the decision was that only virgin women would be spared. Even so, we might accept God wiping out women and children if they had Nephilim blood in them, but there’s nothing in this passage to indicate that this was the reason. Rather, the whole justification is that the people as a whole had earned God’s wrath, and their lives belonged to him anyway.

When critics allege that God is a bloodthirsty, cold, vicious tyrant, they ignore the fact that as God all life is his, and if we use our lives in ways that defy him, he has the right of vengeance. Wouldn’t innocent children go to heaven anyway? When God took the firstborn of Egypt as vengeance for taking the baby boys of Israel, was that less objectionable?

The question for the critics, though, is whether or not they have the right to point fingers at God. If they had the power, many of them would gladly destroy God and all his followers, out of sheer hatred. We know from Bible prophecy that the world will gladly put all followers of Jesus to death by beheading, starvation, and all other forms of atrocity. Even now they condone violence against others just for ideological differences, and turn a blind eye to the suffering and death of millions that they simply don’t like. This very Israel about whom we’ve been reading is a nation many have desired to wipe off the map. Who are all these critics to judge God?

Moses takes care of a lot of last-minute business after ch. 31, but one point worth mentioning for our instruction is in ch. 35: that God required at least two witnesses to convict anyone of a crime worthy of death. How often do we as Christians quickly condemn someone on the basis of nothing but one person’s claims, or worse, by nothing but suspicion or personal dislike? Remember what Jesus said about being judged by the standards we use to judge others.

Finally, the repetition of land grants reminds us that God’s dealings with Israel were, and will be as long as this earth remains, about a people, a land, and a covenant. Yes, the ultimate fulfillment was in Christ; yes, eternity future is spiritual and immortal, though also physical. But at least a thousand years remain for this earth, and we in the body of Christ cannot rush God’s plans or tell him they’re already completed.